Attachment Theory: How Early Patterns Shape Adult Relationships (Without Putting You in a Box)

What is attachment theory, simply?

It’s how we first learned to feel safe and connected with a caregiver—and those early patterns can echo in adult relationships. They’re not fixed. With awareness, regulation, and new experiences, patterns change.

Attachment theory looks at how our earliest bonds teach the nervous system what connection feels like: safe, inconsistent, or risky. Mary Ainsworth’s Strange Situation observed infants during brief separations and reunions; Mary Main extended this work to adults. What matters for therapy is this: the patterns you learned then can show up now—especially under stress—but they’re adaptations, not life sentences. I prefer to talk about tendencies or strategies (anxious, avoidant, fearful) that appear in hard moments, rather than boxing you into a single “style.” People are complex; context matters; and change is absolutely possible.

Mapping your attachment story

This exercise takes 5-7 minutes.

When conflict happens, my body usually…

The story I start telling myself is…

The move I make to feel safe is… (pursue / fix / shut down / joke / disappear)

This move once protected me by…

One flexible alternative I’ll try this week is…

A line I want to hear from a partner/friend is…

A line I can offer them is…

What does “the parent gives the child back to the child” mean?

Through attuned mirroring—naming feelings and staying present—caregivers help a child recognize and regulate their inner world. That early co-regulation becomes a template for emotional self-regulation in adulthood.

The Parent Gives the Child Back to the Child

ATTACHMENT, EMOTIONAL REGULATION, AND REPAIR IN THERAPY

It’s your parents—or whoever your closest attachment figures were—who first teach you how to regulate your emotions. At least, that’s how it’s supposed to work. After all, how could a child possibly know how to do this on their own? Emotional regulation isn’t instinctive. It’s relational—what many of us later relearn in attachment-based therapy and trauma-informed counselling.

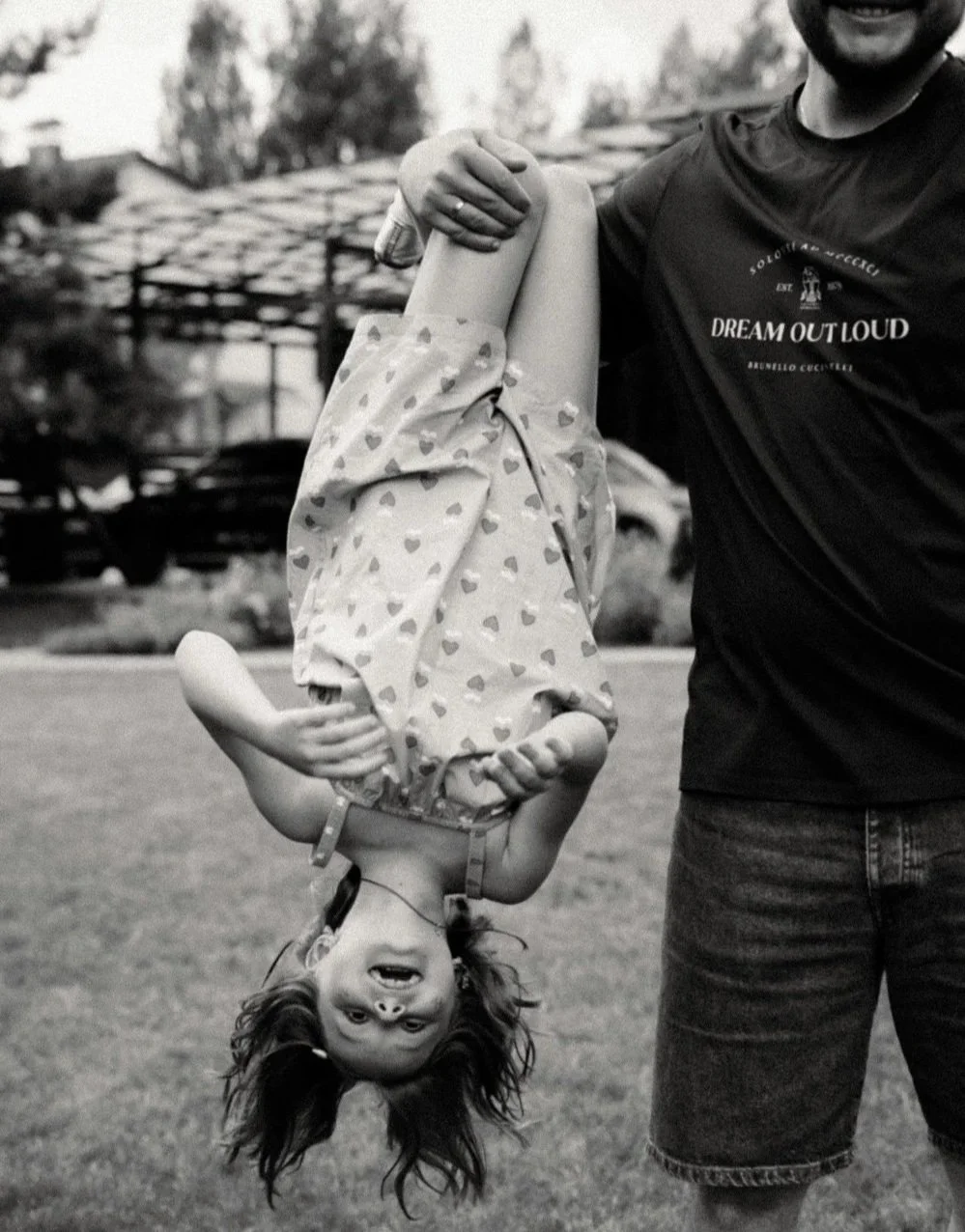

As Daniel Siegel and Allan Schore suggest, and as David Wallin writes in Attachment in Psychotherapy, it is the parent who “gives the child back to the child.” Meaning: it’s through being seen, mirrored, and attuned to, that a child learns to see and understand themselves. When a caregiver mirrors a child’s distress—“You look so sad, sweetheart”—and stays present in that moment, the child learns that their emotional world is real, tolerable, and manageable. That mirroring is the first experience with co-regulation—a foundation we strengthen in individual therapy and inner-child work.

If we are lucky—and I do mean lucky, because it is truly a lottery—the family we’re born into and the geography we happen to live in may offer us parents who can consistently meet those needs. If we’re seen enough, attuned to enough, our capacity to regulate ourselves in adulthood strengthens because our attachment caregivers were there to contain the moments when we were distressed. This is the soil where secure attachment and resilience grow.

But even in the best circumstances, this is never perfect.

Winnicott speaks of “good enough parenting,” a phrase that offers a kind of mercy. The idea isn’t that parents get it right all the time—but that they get it right often enough, in meaningful ways, for a child to develop resilience, trust, and a stable sense of self. This is the same stance I hold in psychotherapy and counselling—repair over perfection.

Some of my patients grew up in homes marked by abuse, neglect, addiction, or chaos—profound failures of care by the very people who were supposed to protect them. Through the safety of our work together, they begin to see how these early ruptures shaped not only their relationships with others, but also the relationship they have with themselves.

Others grew up in homes that were loving in many ways—yet still carry deep wounds from moments of misattunement, emotional absence, or subtle rejection. These are often harder to name because the hurt was wrapped in care. It’s confusing to feel cherished and dismissed, supported and unseen, told you were special while also being told—explicitly or implicitly—that your feelings were “too much.”

This emotional ambiguity leaves a mark.

Many people minimize their pain: “My family wasn’t that bad. Not compared to others. I shouldn’t be struggling.” But trauma isn’t always loud. Sometimes it’s quiet, subtle, or delivered with good intentions. Sometimes it lives in the spaces between what was said and what was never allowed to be felt.

I work with many people from chaotic, openly dysfunctional homes—but I also work with many whose caregivers were both loving and wounding. Parents who were present but emotionally unavailable. Affectionate but critical. Engaged but volatile. They packed lunches and showed up to games, yet never asked how you were feeling. Or told you to stop crying the moment you showed emotion.

Regardless of what you may have been exposed to as a child, more often than not, the damage from these experiences leads to internalization. The child, unable to make sense of what is happening to them, assumes: It must be me. I must be bad. We turn on ourselves before we ever dare turn on our parents—because to acknowledge their failure would feel too dangerous, too disorganizing. It would threaten our survival.

So we carry it. Quietly. For decades, sometimes. Until something in us—through therapy, loss, love, or exhaustion—says: I don’t want to carry this anymore. That moment is often the doorway to attachment-focused psychotherapy, trauma-informed counselling, and relearning emotional regulation and self-compassion in safe therapeutic relationships.

Gentle reflection (5 minutes)

Mirroring memory: When I was upset as a child, the message I got was…

Today’s echo: When I’m distressed now, I tend to… (shut down, appease, explain, fix).

What I needed then: A sentence I wish I’d heard is…

What I can offer now: One sentence I can give myself (or my child/partner) this week is…

Co-regulation plan: When I’m flooded, I’ll down-shift by… (breath, short walk, hand on heart) and then reach out to…

Tip: Write answers in a friend-tone voice. If the critic shows up, rewrite one line as you’d say it to someone you love.

Modern attachment: emotional regulation is the heart

Recent work highlights affect regulation: early relationships sculpt the systems that manage stress and self-soothing (think ANS and neuroendocrine pathways). Through repeated moments of being seen, soothed, and responded to, a child learns to emotionally regulate their inner world. When that process is inconsistent or absent, as adults, emotional regulation is harder and the stress response becomes more reactive. In therapy, rebuilding emotional regulation is often the work.

Therapist translation: Attachment is interactive nervous-system learning. We can relearn it.

Styles vs tendencies

I avoid locking anyone into a single “style.” Instead, notice tendencies under stress:

Anxious-leaning: protest, pursuit, reassurance-seeking, threat language (“don’t leave”).

Avoidant-leaning: shutdown, self-reliance, hyper independence, flooding, minimizing needs, over-indexing on logic.

Fearful/Disorganized-leaning: push-pull, high activation with mistrust, “come close / go away.” One foot on the gas one foot on the break.

These are strategies—they kept you alive. The goal isn’t to erase them; it’s to bring more flexibility.

How therapy helps (what we actually do)

Regulation first: build a library of down-shifts (breath pacing, orientation, proportion).

Make patterns explicit: map triggers → body → story → behaviour.

Practice bids & boundaries: clear asks, time-bound pauses, kind limits.

Earned security: repeated experiences of safe connection (inside therapy and outside) that update the nervous system.

Attachment Theory

Mary Ainsworth conducted the Strange Situation experiment to observe infants' reactions to separation and reunion with their mothers. Mary Main categorized the patterns she observed in babies' reactions to the Strange Situation as secure or insecure and found that mothers' attachment patterns often matched their babies'. She then created subcategories and used the Adult Attachment Interview to explore attachment patterns in mothers and children further.

Understanding that our attachment patterns or tendencies are not fixed is crucial, as these patterns can change over time with personal growth and new relationships. Nevertheless, it's still valuable to examine them, as the attachment patterns we developed with our primary caregivers can influence our behaviour and expectations in the relationships we have today. These early attachment experiences can affect how we choose romantic partners and friends, our behaviour within those relationships, and our decisions about staying in them.

A second point to consider relates to attachment styles. Attachment style is a term used specifically related to how individuals engage in romantic relationships. As mentioned earlier, these styles are distinct from the attachment patterns observed in young children with their primary caregivers. While there may be a connection between our attachment styles and early life experiences, it's a multifaceted matter that requires thorough examination. Attachment is a dynamic process that can evolve over time, so it's essential to avoid categorizing yourself into a single, fixed attachment style based on brief online quizzes.

I view attachment as a set of strategies or tendencies that become apparent in challenging relationship situations, rather than relying solely on the term "attachment style." These strategies or tendencies can manifest as avoidant, fearful, or anxious tendencies. It's crucial to recognize that your attachment style isn't fixed and can't be simply pigeonhole. People and their relationships are intricate; various individuals and circumstances can bring out different tendencies.

FAQs

-

Both can be true. Love without attunement still leaves gaps. Naming the contradiction is often the start of healing.

-

No. Owning impact increases trust and models accountability. Repair can be healing at any point in time.

-

Absolutely—through repeated experiences of safety: therapy, attuned friendships/partnerships, and self-regulation practices.

-

Start with the body (feet, breath, orienting). Then add one sentence of mirroring: “A part of me feels ___. I’m staying.”

-

NO! They’re learned patterns that can change through awareness, regulation, and new relational experiences.

-

They can spark curiosity, but they’re shallow snapshots. Look for tendencies under stress, not a permanent label. Avoid online quizzes.

-

Yes—if you both learn regulation, name needs clearly, and agree on repair rituals, with repetition both can more into more security.

-

You recover faster after conflict, and your bids/boundaries get simpler and kinder. And, you can also quickly identify when you are in your adaptive child.

An Invitation

If you’d like to map your attachment tendencies and build flexible new responses, I offer individual sessions (Vancouver & virtual). We’ll go at a humane pace and practice skills that actually fit your life.